For the winter term of 2020/21, we have given our lecture series a guiding theme, which is: Data & Experimentalism. We inquire into how pragmatist experimentalism can conceptually and practically help re-tooling social scientific practices, and how data may engender, contradict, combine or in other ways be involved in this.

We use this site to present brief reflections of the presentations, asking how the papers relate to data and experimentalism.

Overview of comments

- Experiencing collective accounts of “touch”: Analyzing software maintainers just speak. Talk by Mace Ojala, comment by Estrid

- Cultures of Documentation, ownership and the multiple ways of open biology. Talk by Ana Delgado, comment by Laura

- Civic Data for the Anthropocene. Talk by Tim Schuetz & Shan-Ya Su, comment by Stefan

- Methodischer Experimentalismus im Spiegel von Stasi-Unterlagen. Talk by Olga Galanova, comment by Julie

- Testing: A mode of experimentalism? Talk by Noortje Marres & Tanja Bogusz, comment by Stefan & Estrid

- Digital gaming embodied: Ethnographic serendipity and lucky chances at gaming events. Talk by Ruth Dorothea Eggel, comment by Andreas

- Temporalities of sleep: Sleep, shift work and absence of a ‘natural’ sleep cycle. Talk by Julie Mewes, comment by Ruth

First talk, Mace Ojala: Experiencing collective accounts of “touch”: Analyzing software maintainers just speak

Comment by Estrid

When I think about this term’s RUSTlab Lecture theme “Data and Experimentalism”, I get a light and playful feeling. No question that it is a methodologically and theoretically difficult issue. Yet, it is also hopeful and mobilises a belief in “a future different from the past,” as our dear friend Helen Verran so often states, the horizon of relevant research.

Mace Ojala from the ITU Copenhagen gave the first talk this term by intervening into this light and agreeable feeling. He did so by drawing on the same literature as we drew on when writing our brief introduction to the “Data and Experimentalism” theme. A very helpful intervention.

The talk was on software maintenance. Software maintenance mobilises a quite different atmosphere than the one described about. Maintenance, Mace emphasised, is not innovation; it is not about creating something new. It is not development, since it foresees living with what is already there. Neither is maintenance repair, because most often, they act before a break down. Maintenance is not virtuous, doubly not. First, there is no virtue to maintaining things, it is just annoying if they are not maintained – damaged roads, freezing software, dirty wardrobes. Second, there are phenomena we don’t want maintained: climate change, nationalism, violence, pandemics.

These ideas about maintenance are important also for (data)experimentalism. Mace talked from a broken world perspective (Jackson 2014) where maintenance rather than change seems to be at the horizon of activities. Situated in pandemic times in one of the worldwide largest areas of the industrial ruins of fossil Capitalism, we may learn from Mace’s software maintainers. Generally, he emphasised, they are the ones in organisations who know how everything really works. They become involved in every little corner of an infrastructure across hierarchies and specialist areas. Yet, when they meet up at conference, they don’t want to talk code, but build circles to share their burnout experiences. Mace brought in Puig de la Bellacasa’s (2017) notion of “touch.” Touch connects bodies and materials, and it is mutual: you cannot touch without being touched. Maintainers reach out to everyone, but maybe they all too rarely get in touch with anyone. When they work they are in the way and only when they fail, their presence is noticed. However, in a world of risk and uncertainty, of growth and decay, of fragmentation, dissolution and breakdown (Jackson 2014), the experience and knowledge of maintainers across areas of specialisation, and about the interconnected and multiple character of organisations, practices, politics, may be of great value. Based on American Pragmatism, Marres (2012) has written about issue experts and their involvement in data experiments. They are specialists in particular areas of knowledge, of particular cases. Yet, probably, we need to draw attention also to what we may call “issue-maintainers,” those caring for the continuity of issues.

Issue maintainers may retract some of the lightness of the theme of Data and Experientalism. But they may indeed also help grounding data experiments. A great thanks to Mace Ojala for introducing these thought.

Second talk, Ana Delgado: Cultures of Documentation, ownership and the multiple ways of open biology

Comment by Laura

In this term’s theme, we set out to inquire into the tension between data and experimentalism. We see they are in tension particularly when understanding data according to big data rhetorics and extractivist practices. Data in that understanding is an abstraction that requires little context or knowledge about the socio-material assemblages that lead up to its existence. Experimentalism, then, is the opposite. Inspired by American Pragmatism, Experimentalism requires the first-hand experience, from which knowledge becomes possible. To touch, to feel, to do yourself are modes of knowing in experimentalism.

Ana Delgado’s rich material from almost a decade of studying synthetic biology offers two examples that demonstrate two ways in which biology is opened and thereby offers two different readings of the pair data and experimentalism. (By the way, Ana changed the topic of her talk to reflect on our semester’s theme.)

Ana points to two different groups in tension in synthetic biology: experimentalists and computer scientists. The former argue that data can not be shared easily without knowing first-hand the experimental setting, having research skills and a “feeling for the experiment”. The latter are eager to build standardized platforms where data can be shared to form a “plug and play” biology. Attempts of standardization, however, have failed so far, as the need for the first-hand experience of experimenting prevails, so Ana. In this reading, data stands in contrast to the experience of the experiment.

However, she also offers another reading of data and experimentalism: Aside from academic synthetic biologists, there exists an activist movement of former undergraduate students that have invented DIYbiology. In workshops and with household items they teach interested citizens to employ laboratory methods to do their own inquiries. For example, in the project “BioStrike” where citizens are taught to test soils for antibiotic resistance. The goal of these workshops is less to produce standardized and reproducible results, so Ana, rather than to experiment and experience biology. Photos of soil samples are shared online on “Flickr” and grassroots databases are established.

In this second reading, data and experimentalism are no opponents, but data enables experience, testing and collaboration in a community of activist biologists. Data acts as a facilitator for experience rather than as a standardized representation as it did in the first reading. Data, here, aids to “experience, testing and cooperating” (Bogusz 2018).

I find both examples fit nicely with our attempt to explore further the relation of “Data and Experimentalism”. We must acknowledge their tension in some settings but also the capacity of data to facilitate experience, testing and cooperation that align with Experimentalism. Particularly, the latter is how we approached data in our own data projects as the RUSTlab: as a mode of experience, among others.

Third talk, Tim Schuetz & Shan-Ya Su: Civic Data for the Anthropocene

Comment by Stefan

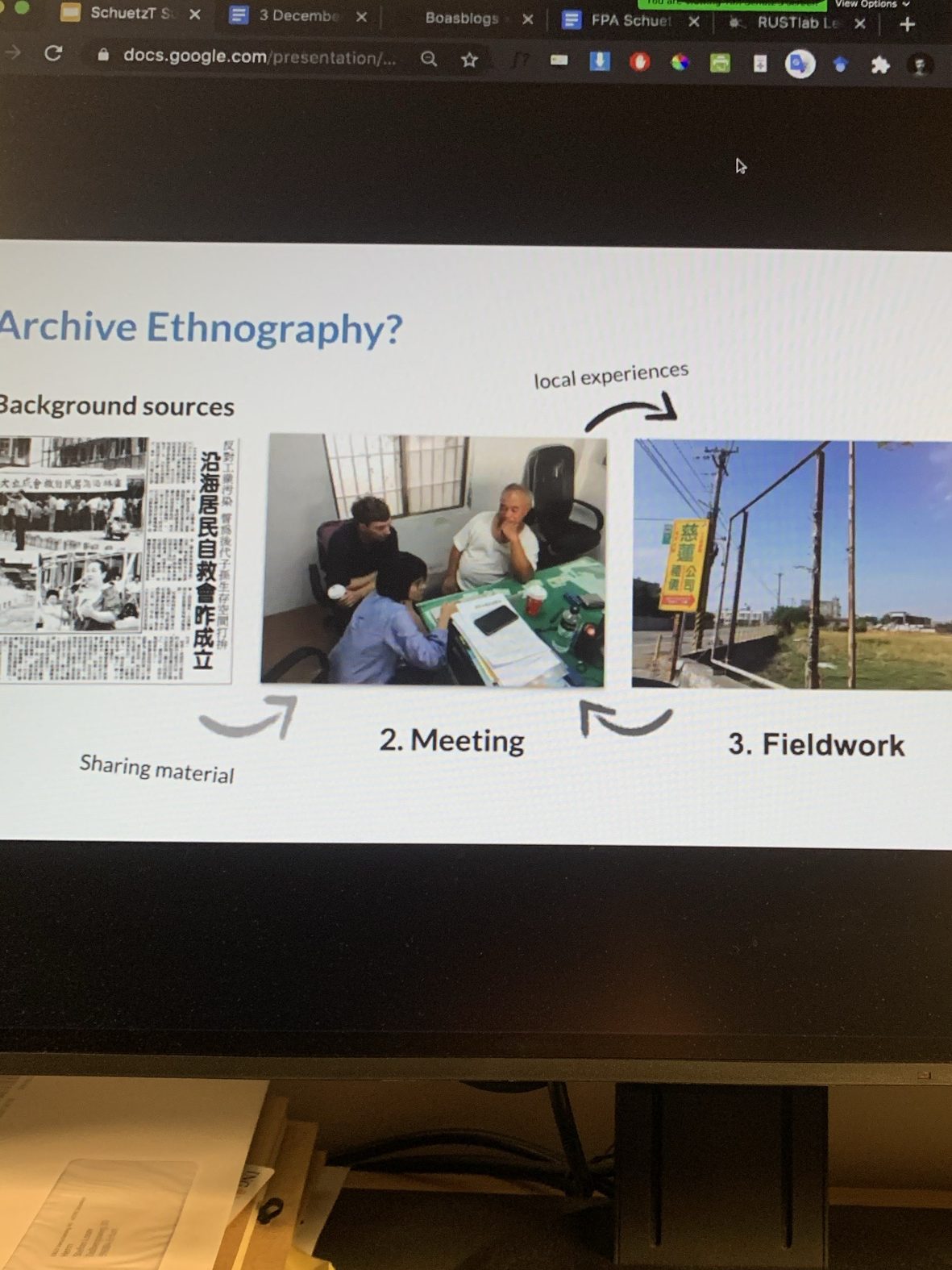

What is the role of digital platforms in facilitating collaborations? Do digital platforms transform what ethnography as such means?

On the 3rd of December, we had the pleasure to get an insight into the extraordinary work of Tim Schuetz & Shan-Ya Su. Tim and Shan-Ya’s paper focused on “Civic Data for the Anthropocene. Following Taiwan’s Formosa plastics”. Most importantly, they introduced us to the notion of archiving as a means to transform what ethnographic, anthropological knowledge production might mean. Digital platforms are at the centre of this discussion, in particular, the Drupal-based “PECE” (the Platform for Experimental, Collaborative Ethnography) network and its instance “Disaster STS“, which is used in the project at hand.

“Formosa Plastics” is a big player in the plastics industry, it is also known as a significant polluter. In the US and Taiwan, advocacy groups, journalists, workers and activists organize to make the company accountable – to document the contamination of the environment around industrial facilities, to make illegal practices debatable, to reflect on dangers and illnesses, to strengthen labour rights, etc.

And here’s the clue: Major actors in the field struggle to organize and archive their material, to share it with other actors on the ground or the extended community of interested actors.

We were introduced to the digital platform as a device to foster collaboration in this context – to enact the global Formosa community. Tim and Shan-Ya showed us the many possibilities for entry points. It was a lot to digest: buttons to follow, digital stories to unpack, a new publication-type in the making, suggestions to include the platform into teaching schemes, among other things. We witnessed a new method emerge – and an entire infrastructure around it.

Key to the discussion from the lens of experimentalism is how the platform presented invites us to re-imagine collaboration. This is about opening up perspectives, mobilizing experts from different fields, academic and non-academic alike, and, perhaps most importantly, to develop and struggle with standard-making. The Disaster STS platform helps to attune to issues on the ground – to particular contexts and their troubles. What is new here, and what I think could be used in many projects, is a particular device that connects hands-on ethnographic encounters with their interpretation and publication. It is a “middleware”, as Joanna Drucker und Patrick Svensson coined it in one post on the PECE platform. To get things going and to make things comparable, the group around Kim and Mike Fortun has developed analytical questions and layers to approach (Kim and Mike being the key driving forces behind the establishment of the PECE world).

As indicated above, the main challenge of this type of research is to decide what is to be included, published for whom, and when to stop collecting things. Regarding the Formosa case, Tim and Shan-Ya introduced a key tension: the vision of making data accessible vs Formosa pressurizing and suing scholars on the ground. This is not a new issue, but due to the platform in place, it scales quite quickly. In this sense, the PECE digital platform connects with traditional themes of ethnography but, as illustrated by the Formosa example, it also transforms how, why and when to conduct ethnography with whom. New avenues for collaborations emerge, no ways to document and/or intervene, which is a compelling argument to engage with such platforms.

What makes this entire project unique is its accessibility. There have been various suggestions to make digital data accessible. There is a mapping of controversies approach (e.g., here), which is used as either a teaching device or a project-based resource, so it is a very focused platform. Then there are repositories that give out tricks and tools for ethnographic investigations, like the Amsterdam Digital Methods Initiative and the Ethnographic Inventory. This is great to get inspiration. Latour (and the broader AIME team) published a comprehensive platform that aimed to develop the argument of a book, which also indicates that this was a somewhat limited and even restricted platform, due to its focus on being useful in the sense of the book’s logic. Recently, the Feral Atlas was published that wants to attune to more-than-human histories by way of a comprehensive and brilliantly designed platform. The latter platform perhaps is the one that comes the closest to the PECE and Disaster initiatives, even though the platforms are very different. The Feral Atlas, in its essence, is a closed archive, while the PECE platform aims for open and free access. This is what Tim and Shan-Ya highlighted convincingly; this is where from my point of view, the future of digital ethnography should lie: in open and creative devices. Tinkering is part of this endeavour and adds value to it. It is worth thinking about the modes of collaborations that are dis/enabled by platforms.

If you want to see an easy (and completely open) example of a Disaster STS outcome, check this out: chemical plants in Cancer Valley and their Covid-19 story (scroll down to start a tour). The Formosa plastics story is part of this as well.

Vierter Vortrag, Olga Galanova: Methodischer Experimentalismus im Spiegel von Stasi-Unterlagen

Kommentiert von Julie

In a world where there is as much complexity and contingency as there is in our world, it is true both that action is necessary and that action must be experimental, a trying. Experimental method […] is then something different from the bare fact of the omnipresence of uncertain trial in all action. The difference is that between the experiment which is aware of what it is about and experiment which ignores conditions and consequences.

(Dewey/Childs, The Underlying Philosophy of Education

[1933], LW.8.94.)

Am 17. Dezember 2020 gewährte Olga Galanova in ihrem deutschsprachigen Vortrag Einblicke in ein faszinierendes Forschungsfeld und explorierte drei experimentelle Zugänge zu und mit ihren Forschungsdaten, Anrufmitschnitten von DDR-Bürger*innen des Ministeriums für Staatssicherheit.

Nach Stationen in Nishnij Nowgorod, Dresden und Bielefeld ist die promovierte Soziologin seit 2020 Projektleiterin des am Lehrstuhl für Wissensanthropologie und Kulturpsychologie ansässigen DFG-geförderten Projekts „Anrufe beim MfS: Adressatenzuschnitte als Vollzug gegenseitiger Beobachtung”. Olga ist zudem Lehrbeauftrage am Lehrstuhl, Dozentin an der Hochschule für Polizei sowie, last but not least, Teammitglied des RUSTLabs.

Fokus ihres Vortrags war die Frage, was sie aus ihrem diversen Datenmaterial zum Thema Experimentalismus beitragen könne. Auf das diessemestrige Oberthema „Daten und Experimentalismus” bezog sich Olgas Vortrag auf drei unterschiedlichen Ebenen der bewussten Reflexion im Sinne Deweys:

a) den experimentellen Praktiken der Fallkonstruktion der Staatssicherheit als Methodologien des Felds,

b) den kreativen, vielfältigen Umgangsarten mit der Behörde seitens der Bürger*innen sowie

c) dem, auf Methoden der ethnomethodologischen Konversationsanalyse gestützten, experimentellen methodologischen Zugang der Forscherin selbst.

Im ersten Teil a) verwies Olga auf die experimentierende Fallkonstruktion des MfS. Diese lasse sich als eine Form der (Proto-)sozialforschung mit vielfältigen Bezügen zu qualitativen Methoden wie hermeneutischen Text- und Bildanalysen, Inhaltsanalysen, der Biographieforschung oder der Netzwerkanalyse verstehen. Diese Kontinuitätsbeziehung zwischen soziologischem und alltäglich-geheimdienstlichem Erkenntnisprozess zusammen zu denken, ermöglicht eine Reflexion darüber, wie verschiedene Daten den Forschungsprozess leiteten und was die Daten mit dem Forschenden machten.

Im zweiten Teil des Vortrags b) unterstrich Olga, wie heterogen Interaktionen von DDR-Bürger*innen mit dem MfS sein konnten. Eine Analyse von Anrufmitschnitten widerlege das Vorurteil einer alleinig vom MfS ausgehenden Beobachtung. Immer wieder fragten DDR-Bürger*innen beispielsweise den MfS auch über ihre Arbeit und Beobachtungsziele an, äußerten Beschwerden oder denunzierten andere Bürger*innen.

Anhand des kleinen Einblicks in ihre empirischen Daten c) verdeutlichte Olga im dritten Teil ihren methodischen Zugang und warum dieser als experimentell zu verstehen sei. Im Sinne des Eingangszitats handle es sich um ein gerichtetes, bewusstes Experiment mit dem Ziel, Methoden am Forschungsgegenstand selbst zu entwickeln und daran anzupassen, da diese in einen einzigartigen Forschungskontext eingebunden seien. Es gelte, die Selbstreflexion über diese Methoden zu verbessern und die methodische Weiterentwicklung selbst voranzutreiben sowie die Daten für die interdisziplinäre Diskussion zugänglich zu machen.

Fifth Talk: Noortje Marres (Warwick) & Tanja Bogusz (Kassel): Testing: A mode of experimentalism?

Comment by Stefan & Estrid

On Thursday, the January 7th, we had the privilege to host two leading international figures in neopragmatist research. Noortje Marres and Tanja Bogusz were invited to a discussion on the role of testing in experimentalist, pragmatist thinking and doing. The speakers offered us an embedding in theoretical discourses based on tangible contemporary issues. The approach showed its strengths here because Noortje and Tanja, considering apparently difficult practical problems, pushed towards a joint realisation of intervention with reflection.

Both presenters have published extensively on the advancement of pragmatist thinking, yet two recent publications were at the heart of the discussion: Marres‘s and Stark‘s (2020) recent paper “Put to the test: For a new sociology of testing” and Bogusz‘ monograph “Experimentalism and Sociology. From crisis to experience” (this English version of the 2018 German book “Experimentalismus und Soziologie” is in press). Both authors have thoroughly reworked Dewey’s Pragmatism and brought it up to date, Noortje particularly by attending to digitalisation and Tanja by spelling out Dewey’s theory in a sociologically coherent way.

Noortje started out by discussing experimentation as a re-distribution of the capacity to articulate what is at stake. A key challenge in this is how to organise situations that enable such articulations. The focus on the organisation of settings of experimentation works as an act of denaturalising, i.e. that the articulation of a concern is not just about opening your mouth and expressing a problem. Socio-material settings must be organised that make the articulation of problems at stake possible. Tanja added to this by emphasising that experiments have the crucial capacity to interrupt routines of action (or habits), which are then channelled by actors via concrete, that is, situated and embodied procedures. She emphasised that more than interrupting routines, experiments furthermore produce knowledge and participation, and suggested a differentiation between three modes of pragmatist research: experience, testing and cooperation.

Both speakers agreed that experimentation is a genuinely democratic-theoretical and indeed practical work. While Tanja emphasised the importance of uncertainty and that experimentation is a competent reaction to uncertainty, Noortje emphasised attention to “at stakeness”. For our own engagements with data and experimentalism we found this discussion particularly fruitful. Like Tanja – or indeed inspired by her work – we have taken a point of departure in data experiments as an instrument to engage with uncertainty. Yet, “at stakeness” invites us to look at rather what is at stake, who defines what is at stake and how to react to it – and thus what is certain and uncertain – is a question that needs attention, which is precisely what Tanja also emphasised during the discussion.

Uncertainties may translate into ecologies of testing and the account for differences. In the open discussion, it became apparent that those assembled were under no illusions about pragmatism’s current role. The approach is not in a hegemonic position. But it nevertheless showed itself to be responsive. This became clear based on the omnipresent Corona crisis. Tanja suggested differentiating between “preparedness” and “prevention”. Especially in Western (or, to be more precise: Berlin) policies, a reactive approach to Covid-19 dominates, and strategic processing of individual problems, or preparation. A higher-level mode of dealing with the virus – preparedness – may be more helpful, i.e. making actors reflect on their recent experiences and everyday experiments with the crisis to collaborate strategically. This was just one example where the power of the approach becomes apparent.

Sixth Talk, Ruth Dorothea Eggel (Bonn): Digital gaming embodied: Ethnographic serendipity and lucky chances at gaming events

Comment by Andreas

On Thursday, January 14th we had the pleasure of getting an insight into cultural anthropologist Ruth Dorothea Eggel’s dissertation project that she is currently working on at the University of Bonn. In her talk titled “Digital gaming embodied: Ethnographic serendipity and lucky chances at gaming events” Ruth presented her research on how digital computer gaming culture is embodied at large scale gaming events (and vice versa) to the lab.

The gaming mega-events Ruth is inquiring into are characterized by the merging of digital and non-digital practices and so blurring the borders between “online” and “offline”. These hybrid fields thus pose new challenges for digital anthropology and digital (ethnographic) methods. The investigation of these fairly uncharted and ever-changing socio-technological worlds calls for a re-tooling of existing social scientific practices, whose new experimentalist approaches necessarily involve digital data as modes of inquiry.

To conduct research in this interconnected field Ruth used a variety of combined digital and non-digital methods, i. e. extensive participant observation offline, continuous participant observation online, situative and semi-structured interviews. To gain a “thick presence,” her research design was multimodal and multi-sited, for which many methods in her ethnographic toolbox had to be tweaked to fit the respective settings.

Ruth focused her presentation on the aspect of occurring serendipity (unplanned fortune discovery of something originally not looked for) while doing fieldwork and its incorporation into ethnographic research. According to Ruth, ‘lucky chance’ moments, when something unforeseen but desirable happens are an integral part of mega gaming events, i.e. a spontaneous conversation which leads to a job opportunity. In the case of the gaming events, these moments are not due to luck, but the interactions made as they increase the chance of ‘fortunate coincidences’, so Ruth. These moments cannot be forced, but one can up the chance they happen. According to Ruth, at and around gaming events, a shared and ritualized playful attitude is fostered: Any given situation can be made into a quest and be solved like one. This implies a high degree of liminality; group boundaries are very permeable in the context of gaming events, as strangers are often asked to be team players as part of a quest.

Ruth illustrated her findings with a story from her fieldwork at a Gamescom event. On the way there, she incidentally got into a train with a group of event visitors. When Ruth lost her cell phone (an indispensable item at a gaming event!), and one member of the group found it, it was instantly considered a group task to return it to the rightful owner. In return, Ruth gave a spare Gamescom ticket to one of the group’s members and was subsequently included in their collective ‘quest’ to arrive at the event location despite train cancellation.

The playful attitude, which ludically connects people, a more outgoing “event persona” and various organizational arrangements to attend the large scale gaming events, lead to numerous lucky chance occurrences, so Ruth.

According to her, the Senecan dictum – “luck is what happens when preparation meets opportunity” – also holds true for scientific researchers. In science’s historical course, unplanned discoveries are neither seldom nor unpopular, think for example of Penicillin. Such instances of lucky chances, which are more than the sum of its parts, do not merely fall onto people, but are produced or instead made more likely to happen via preparation. With reference to Petro Medina Ruth put forward the notion of serendipity as an intentioned/directed/strategic happy accident.

For Ruth, serendipity in ethnographic research can be considered and to a degree provoked as the outcome of a lucky chance sequence. Not looking for something specific, but having a playful attitude can in this manner lead to something unexpected (indeterminacy of outcomes), as it invites coincidental moments of the unknown.

Ruth closed on the takeaway that ethnographers cannot make themselves lucky. They may offer potential lucky chances to others, increasing the possibility of a sequence of lucky chances: Sometime after Ruth’s visit to Gamescom a girl reached out to her unacquaintedly as an additional interviewee for her research project. She had gotten Ruth’s card from a member out of the group who got Ruth her phone back on the train and in turn, received an extra ticket and then included her in their travel party on the way to the Gamescom event after which they exchanged contacts… Level up!

The discussion following the presentation pointed out that Ruth’s talk was critical and compatible with our current pragmatism theme. One is usually focused on designing research settings expecting a particular outcome. But one might instead set up a design to give enough space for something unexpected but insightful to happen out of the situative circumstances – or not, and in the latter case just “play again”.

Comment Mewes: “Temporalities of sleep: Sleep, shift work and absence of a ‘natural’ sleep cycle”

Comment by Ruth

We all have to do it. Many of us yearn for it: Sleep is critical to all of our lives, yet it gets little attention from social sciences. Julie Mewes delightful talk on “Temporalities of sleep: Sleep, shift work and absence of a ‘natural’ sleep cycle” on January 28th 2021, addressed sleeping strategies and tools, following this semester’s theme of “data & experimentalism”.

Mainly interested in sociomaterialities and devices of sleep, Julie chose a research field with extreme sleeping conditions: Focussing on healthcare professionals in shift work above the polar cycle poses a challenging – but even more interesting – setting for sleep cycles in multiple ways. First, the northern location holds its own implications for sleep, as natural light above the polar cycle doesn’t support a “natural” day-night cycle during most of the year. Second, the hospital’s work environment with rotating shifts messes up any regularity of sleep cycles. Third, healthcare professionals hold a double role between medical expertise and self-care, often creating a gap between health advice given to patients and health advice practised.

Julie argued that social sciences showed hardly any interest in bodies in their dormant state for a long time, considering it a private matter. In the 2nd half of the 20th century, medical advice on improving sleep started, focusing on the “sleep of others”. Subsequently, with a shift towards individual responsibility of body and self, the “sleep of ourselves” increasingly conceptualized sleep as something to optimize and improve, e.g. with sleep tracking apps. Julie argued that even more recent developments try to support sleep everywhere at any time. This “sleep of anytime” further shifts responsibility for good sleep from individuals to tools and devices that are meant to organize and enhance sleep.

Following the semester’s theme, Julie discussed her experimental way of ethnographically approaching the intimate settings of sleep. Using “interviews to the double” (Nicolini 2009,2017), she reconstructed sleep practices to make up for the problem that observing people during their sleep is hardly possible for ethnographers. Closing the gap between practices and talking about practices “interviews to the double” try to re-enact the everyday practices surrounding sleep, recreating as many details as possible. Following this method, Julie represented reconstructed field notes, narrating the sleeping routines of interviewees. This translation vividly re-synchronizes and re-embeds the narratives of practice into daily life, to give us insight into intimate sleep routines. E.g. we heard about Nina, who doesn’t try to follow a sleeping rhythm but sleeps in two bouts during the day after a shift, using tools and devices like light-hearted TV-shows to calm down after a shift, or audio-books to fall asleep.

Because healthcare workers in arctic regions in Norway have to become experts in the “sleep of anytime” within their extreme work-life-sleep-balance, Julie especially focused on the means and devices people use to manage their sleep cycles and patterns. These social and material “Zeitgeber”-tools enable a systematization of sleep cycles, giving time or rhythms to support sleep anytime and everywhere. Anne, another interviewee, uses artificial lights and blinds or curtains and sleeping masks to imitate a light cycle to “fool her brain and body” into a regular sleeping rhythm. Mia tries to get at least six to seven hours of sleep, coordinating it also to be able to spend time with friends and family with regular working hours, stressing the – often overlooked – social aspects of sleep. The sleep devices used include a wide range of means, from looking out of a window to more high-tech devices like sleep trackers. They are part of different strategies developed individually to find good sleep. In the search for what it is, that creates a “sleepability” for people, Julie summed up, that good sleep doesn’t have to follow normative circumstances of a full night’s rest. It is the quality of sleep that matters most. More challenging conditions also lead to more managing efforts by individuals. These strategies are partially transferable to other settings, showing different ways to organize sleep when natural light or work cycles don’t support it.

Discussing Julie’s experimental approach, we talked about the difficulty of studying subjects like sleeping habits ethnographically and how “interviews to the double” could be of service to ethnography in such fields. Translating narratives to reconstructed fieldnotes might be problematic in creating the illusion these situations were directly observed. Yet it enables Julie to analyze sleeping practices, that otherwise couldn’t be observed at all. Thus, it is an experimental way of writing about the data collected in the field, which utilizes storytelling to make the different sleep tangible and comprehensible strategies.